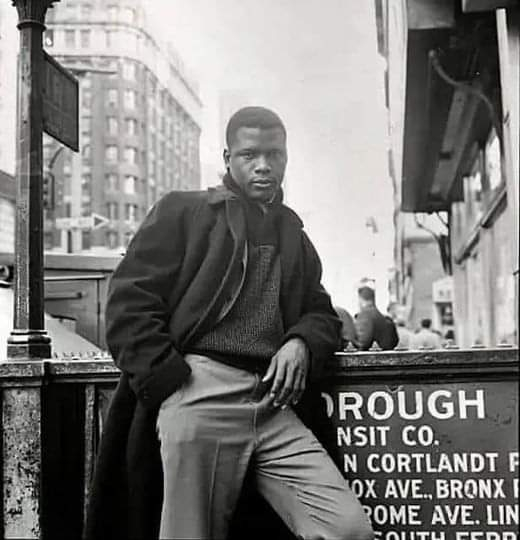

Sidney Poitier was a 20 year old dishwasher in NYC. He came from the Bahamas and could only read 3rd grade level, having great trouble with 3 syllable words. He lost his dish washing job, so he looked in the want ads and was about to throw the newspaper into the trash box on the street when he read: Actors Wanted.

The 'wanted' seemed like an invitation, so he walked to the address, was given a two page scene to read by a large man. Poitier slowly read word by word in his Caribbean accent. The large man grabbed him by the belt and collar and pushed him to the door saying, "Stop wasting people's time. You can't speak and you can't read.

Go back to dish washing." Walking to the bus stop Poitier stopped on the street thinking, "How did he know I was a dishwasher?" Poitier said: "I realized that was his perception of me. No value but something I could do with my hands. Even though he was correct in his anger to characterize me that way, I was deeply offended. I said to myself, 'I have to rectify that.' "I decided right then on that street, that I was going to be an actor just to show him he was wrong about me. I had to take the responsibility to change how people perceived me.

I continued as a dishwasher, but I began to work on myself."

Poitier auditioned at the American Negro Theater in Harlem, hoping to get into classes there. He didn't know that one could buy books with plays in them, so he memorized an article in True Confessions magazine.

He wasn't accepted, but Sidney said, "I'll be your janitor for free if you let me study here." The school accepted that deal. Months later, he was told he had no gift for acting and had to leave. Unknown to Poitier, three fellow students that liked him went to the head-master and asked her to give him a walk on in the next play. She said, "No, but I'll make him the understudy for the lead. (She had no intention to use him).

However, the night of the play, the lead, Harry Belafonte, had to help his janitor father carry out the six heavy boxes of furnace ashes, and it had to be done that night. So Poitier went on, knew his lines and did he best he could. In the theater that night was a producer that offered him a bit part in his next play. His character was the first to speak as an excited man who has to tell some news in the first scene, and that was all.

Poitier said, "When I looked out through a peephole at the 1,200 people waiting for the play to begin, I became paralyzed with fear. "I ran out on stage and started with my 7th line first. The other actor's eyes bulged out, but he came up with the right answer. We skipped around lines, then my character left the stage and that was my only scene. The audience didn't know the play, so they liked my confused, excited character.

"However, walking back to the room I was renting, I decided to give up on acting. I bought four newspapers on the way home and was surprised that I was mentioned favorably in three of them, like: 'Who was that funny kid that came on at the beginning?' So I decided to continue acting." After a few small parts in small movies, it was 1954. Sidney Poitier was sent to an audition for a movie by an agent named Martin Baum, but was not Poitier's agent.

Poitier read a scene in front of the producers, they wanted him and gave him a full script to take home. Poitier's character was a janitor who saw a crime committed by gangsters. To keep him quiet, the gangsters kill his daughter. And he stays quiet. Poitier said, "I really hated it. At that time, I had no objections to playing a janitor, but I hated the idea of a father not taking action on the gangsters. The janitor permits what the gangster do to him. To the writers it's just a plot point, but I can't play that because I have a father. And I know my father would never be like that. And as a father myself, I would never be able to NOT attack those gangsters. I want to do movies that show who I am as a human being."

Poitier called Martin Baum who said they will pay $750 for the part. ($7,000 today). He told Baum, " I read it and I can't play it," and explained why. Baum said, “That’s why you don't want to do this? You need that money don't you?" Poitier desperately needed the money. He had to pay the hospital $75 for his 2nd daughter's birth. But didn't take the part. Poitier said, "That speaks to who I was then and still am. And who I am is my father's son. I saw how he treated my mother and family. I know how to be a decent human being.

So I pawned my furniture, such as it was, got $75 and paid the hospital. Then I went back to dish washing. "Months later, Martin Baum called me and invited me to his office and said, "I have never been able to understand why you turned down that job. I told him why again, but I don't know if he understood it.

But Martin said, 'I have decided that anyone as crazy as you are, I want to be their agent.' He's been my agent till now." Poitier won an Academy Award for Best Actor for 'Lilies of the Field' in 1963. Five years later, Sidney Poitier was offered the lead in 'In the Heat of the Night' to be produced by Walter Mirisch (West Side Story, The Magnificent 7) Poitier said, "When I read the script, I said, 'Walter I can’t play this. The scene requires me to be slapped by a wealthy man and I just look at him fiercely and walk away. That is not very bright in today's culture. It's dumb.

"This is 1968. You can't do that. The black community will look at that and be appalled, because the human response would be different. You certainly won't do the movie with me this way. 'If I do this movie, I insist to respond as a human being; he pops me and I pop him right back. If you want me to play it, you will put that in writing. Also in writing you will say 'If this picture plays in the south, that scene is never removed.' Walter said, 'Yeah, I promise you that and I'll put it in writing.' "But being the kind of guy Walter is, his handshake and his word are the same, so I didn't need to have it in writing, and he kept his word. That scene made the movie. Without it, the movie wouldn't have been as popular."

'In the Heat of the Night' won five Academy Awards: Best Picture - Best Screenplay.

Sidney Poitier was a 20 year old dishwasher in NYC. He came from the Bahamas and could only read 3rd grade level, having great trouble with 3 syllable words. He lost his dish washing job, so he looked in the want ads and was about to throw the newspaper into the trash box on the street when he read: Actors Wanted.

The 'wanted' seemed like an invitation, so he walked to the address, was given a two page scene to read by a large man. Poitier slowly read word by word in his Caribbean accent. The large man grabbed him by the belt and collar and pushed him to the door saying, "Stop wasting people's time. You can't speak and you can't read.

Go back to dish washing." Walking to the bus stop Poitier stopped on the street thinking, "How did he know I was a dishwasher?" Poitier said: "I realized that was his perception of me. No value but something I could do with my hands. Even though he was correct in his anger to characterize me that way, I was deeply offended. I said to myself, 'I have to rectify that.' "I decided right then on that street, that I was going to be an actor just to show him he was wrong about me. I had to take the responsibility to change how people perceived me.

I continued as a dishwasher, but I began to work on myself."

Poitier auditioned at the American Negro Theater in Harlem, hoping to get into classes there. He didn't know that one could buy books with plays in them, so he memorized an article in True Confessions magazine.

He wasn't accepted, but Sidney said, "I'll be your janitor for free if you let me study here." The school accepted that deal. Months later, he was told he had no gift for acting and had to leave. Unknown to Poitier, three fellow students that liked him went to the head-master and asked her to give him a walk on in the next play. She said, "No, but I'll make him the understudy for the lead. (She had no intention to use him).

However, the night of the play, the lead, Harry Belafonte, had to help his janitor father carry out the six heavy boxes of furnace ashes, and it had to be done that night. So Poitier went on, knew his lines and did he best he could. In the theater that night was a producer that offered him a bit part in his next play. His character was the first to speak as an excited man who has to tell some news in the first scene, and that was all.

Poitier said, "When I looked out through a peephole at the 1,200 people waiting for the play to begin, I became paralyzed with fear. "I ran out on stage and started with my 7th line first. The other actor's eyes bulged out, but he came up with the right answer. We skipped around lines, then my character left the stage and that was my only scene. The audience didn't know the play, so they liked my confused, excited character.

"However, walking back to the room I was renting, I decided to give up on acting. I bought four newspapers on the way home and was surprised that I was mentioned favorably in three of them, like: 'Who was that funny kid that came on at the beginning?' So I decided to continue acting." After a few small parts in small movies, it was 1954. Sidney Poitier was sent to an audition for a movie by an agent named Martin Baum, but was not Poitier's agent.

Poitier read a scene in front of the producers, they wanted him and gave him a full script to take home. Poitier's character was a janitor who saw a crime committed by gangsters. To keep him quiet, the gangsters kill his daughter. And he stays quiet. Poitier said, "I really hated it. At that time, I had no objections to playing a janitor, but I hated the idea of a father not taking action on the gangsters. The janitor permits what the gangster do to him. To the writers it's just a plot point, but I can't play that because I have a father. And I know my father would never be like that. And as a father myself, I would never be able to NOT attack those gangsters. I want to do movies that show who I am as a human being."

Poitier called Martin Baum who said they will pay $750 for the part. ($7,000 today). He told Baum, " I read it and I can't play it," and explained why. Baum said, “That’s why you don't want to do this? You need that money don't you?" Poitier desperately needed the money. He had to pay the hospital $75 for his 2nd daughter's birth. But didn't take the part. Poitier said, "That speaks to who I was then and still am. And who I am is my father's son. I saw how he treated my mother and family. I know how to be a decent human being.

So I pawned my furniture, such as it was, got $75 and paid the hospital. Then I went back to dish washing. "Months later, Martin Baum called me and invited me to his office and said, "I have never been able to understand why you turned down that job. I told him why again, but I don't know if he understood it.

But Martin said, 'I have decided that anyone as crazy as you are, I want to be their agent.' He's been my agent till now." Poitier won an Academy Award for Best Actor for 'Lilies of the Field' in 1963. Five years later, Sidney Poitier was offered the lead in 'In the Heat of the Night' to be produced by Walter Mirisch (West Side Story, The Magnificent 7) Poitier said, "When I read the script, I said, 'Walter I can’t play this. The scene requires me to be slapped by a wealthy man and I just look at him fiercely and walk away. That is not very bright in today's culture. It's dumb.

"This is 1968. You can't do that. The black community will look at that and be appalled, because the human response would be different. You certainly won't do the movie with me this way. 'If I do this movie, I insist to respond as a human being; he pops me and I pop him right back. If you want me to play it, you will put that in writing. Also in writing you will say 'If this picture plays in the south, that scene is never removed.' Walter said, 'Yeah, I promise you that and I'll put it in writing.' "But being the kind of guy Walter is, his handshake and his word are the same, so I didn't need to have it in writing, and he kept his word. That scene made the movie. Without it, the movie wouldn't have been as popular."

'In the Heat of the Night' won five Academy Awards: Best Picture - Best Screenplay.

The 'wanted' seemed like an invitation, so he walked to the address, was given a two page scene to read by a large man. Poitier slowly read word by word in his Caribbean accent. The large man grabbed him by the belt and collar and pushed him to the door saying, "Stop wasting people's time. You can't speak and you can't read.

Go back to dish washing." Walking to the bus stop Poitier stopped on the street thinking, "How did he know I was a dishwasher?" Poitier said: "I realized that was his perception of me. No value but something I could do with my hands. Even though he was correct in his anger to characterize me that way, I was deeply offended. I said to myself, 'I have to rectify that.' "I decided right then on that street, that I was going to be an actor just to show him he was wrong about me. I had to take the responsibility to change how people perceived me.

I continued as a dishwasher, but I began to work on myself."

Poitier auditioned at the American Negro Theater in Harlem, hoping to get into classes there. He didn't know that one could buy books with plays in them, so he memorized an article in True Confessions magazine.

He wasn't accepted, but Sidney said, "I'll be your janitor for free if you let me study here." The school accepted that deal. Months later, he was told he had no gift for acting and had to leave. Unknown to Poitier, three fellow students that liked him went to the head-master and asked her to give him a walk on in the next play. She said, "No, but I'll make him the understudy for the lead. (She had no intention to use him).

However, the night of the play, the lead, Harry Belafonte, had to help his janitor father carry out the six heavy boxes of furnace ashes, and it had to be done that night. So Poitier went on, knew his lines and did he best he could. In the theater that night was a producer that offered him a bit part in his next play. His character was the first to speak as an excited man who has to tell some news in the first scene, and that was all.

Poitier said, "When I looked out through a peephole at the 1,200 people waiting for the play to begin, I became paralyzed with fear. "I ran out on stage and started with my 7th line first. The other actor's eyes bulged out, but he came up with the right answer. We skipped around lines, then my character left the stage and that was my only scene. The audience didn't know the play, so they liked my confused, excited character.

"However, walking back to the room I was renting, I decided to give up on acting. I bought four newspapers on the way home and was surprised that I was mentioned favorably in three of them, like: 'Who was that funny kid that came on at the beginning?' So I decided to continue acting." After a few small parts in small movies, it was 1954. Sidney Poitier was sent to an audition for a movie by an agent named Martin Baum, but was not Poitier's agent.

Poitier read a scene in front of the producers, they wanted him and gave him a full script to take home. Poitier's character was a janitor who saw a crime committed by gangsters. To keep him quiet, the gangsters kill his daughter. And he stays quiet. Poitier said, "I really hated it. At that time, I had no objections to playing a janitor, but I hated the idea of a father not taking action on the gangsters. The janitor permits what the gangster do to him. To the writers it's just a plot point, but I can't play that because I have a father. And I know my father would never be like that. And as a father myself, I would never be able to NOT attack those gangsters. I want to do movies that show who I am as a human being."

Poitier called Martin Baum who said they will pay $750 for the part. ($7,000 today). He told Baum, " I read it and I can't play it," and explained why. Baum said, “That’s why you don't want to do this? You need that money don't you?" Poitier desperately needed the money. He had to pay the hospital $75 for his 2nd daughter's birth. But didn't take the part. Poitier said, "That speaks to who I was then and still am. And who I am is my father's son. I saw how he treated my mother and family. I know how to be a decent human being.

So I pawned my furniture, such as it was, got $75 and paid the hospital. Then I went back to dish washing. "Months later, Martin Baum called me and invited me to his office and said, "I have never been able to understand why you turned down that job. I told him why again, but I don't know if he understood it.

But Martin said, 'I have decided that anyone as crazy as you are, I want to be their agent.' He's been my agent till now." Poitier won an Academy Award for Best Actor for 'Lilies of the Field' in 1963. Five years later, Sidney Poitier was offered the lead in 'In the Heat of the Night' to be produced by Walter Mirisch (West Side Story, The Magnificent 7) Poitier said, "When I read the script, I said, 'Walter I can’t play this. The scene requires me to be slapped by a wealthy man and I just look at him fiercely and walk away. That is not very bright in today's culture. It's dumb.

"This is 1968. You can't do that. The black community will look at that and be appalled, because the human response would be different. You certainly won't do the movie with me this way. 'If I do this movie, I insist to respond as a human being; he pops me and I pop him right back. If you want me to play it, you will put that in writing. Also in writing you will say 'If this picture plays in the south, that scene is never removed.' Walter said, 'Yeah, I promise you that and I'll put it in writing.' "But being the kind of guy Walter is, his handshake and his word are the same, so I didn't need to have it in writing, and he kept his word. That scene made the movie. Without it, the movie wouldn't have been as popular."

'In the Heat of the Night' won five Academy Awards: Best Picture - Best Screenplay.

Sidney Poitier was a 20 year old dishwasher in NYC. He came from the Bahamas and could only read 3rd grade level, having great trouble with 3 syllable words. He lost his dish washing job, so he looked in the want ads and was about to throw the newspaper into the trash box on the street when he read: Actors Wanted.

The 'wanted' seemed like an invitation, so he walked to the address, was given a two page scene to read by a large man. Poitier slowly read word by word in his Caribbean accent. The large man grabbed him by the belt and collar and pushed him to the door saying, "Stop wasting people's time. You can't speak and you can't read.

Go back to dish washing." Walking to the bus stop Poitier stopped on the street thinking, "How did he know I was a dishwasher?" Poitier said: "I realized that was his perception of me. No value but something I could do with my hands. Even though he was correct in his anger to characterize me that way, I was deeply offended. I said to myself, 'I have to rectify that.' "I decided right then on that street, that I was going to be an actor just to show him he was wrong about me. I had to take the responsibility to change how people perceived me.

I continued as a dishwasher, but I began to work on myself."

Poitier auditioned at the American Negro Theater in Harlem, hoping to get into classes there. He didn't know that one could buy books with plays in them, so he memorized an article in True Confessions magazine.

He wasn't accepted, but Sidney said, "I'll be your janitor for free if you let me study here." The school accepted that deal. Months later, he was told he had no gift for acting and had to leave. Unknown to Poitier, three fellow students that liked him went to the head-master and asked her to give him a walk on in the next play. She said, "No, but I'll make him the understudy for the lead. (She had no intention to use him).

However, the night of the play, the lead, Harry Belafonte, had to help his janitor father carry out the six heavy boxes of furnace ashes, and it had to be done that night. So Poitier went on, knew his lines and did he best he could. In the theater that night was a producer that offered him a bit part in his next play. His character was the first to speak as an excited man who has to tell some news in the first scene, and that was all.

Poitier said, "When I looked out through a peephole at the 1,200 people waiting for the play to begin, I became paralyzed with fear. "I ran out on stage and started with my 7th line first. The other actor's eyes bulged out, but he came up with the right answer. We skipped around lines, then my character left the stage and that was my only scene. The audience didn't know the play, so they liked my confused, excited character.

"However, walking back to the room I was renting, I decided to give up on acting. I bought four newspapers on the way home and was surprised that I was mentioned favorably in three of them, like: 'Who was that funny kid that came on at the beginning?' So I decided to continue acting." After a few small parts in small movies, it was 1954. Sidney Poitier was sent to an audition for a movie by an agent named Martin Baum, but was not Poitier's agent.

Poitier read a scene in front of the producers, they wanted him and gave him a full script to take home. Poitier's character was a janitor who saw a crime committed by gangsters. To keep him quiet, the gangsters kill his daughter. And he stays quiet. Poitier said, "I really hated it. At that time, I had no objections to playing a janitor, but I hated the idea of a father not taking action on the gangsters. The janitor permits what the gangster do to him. To the writers it's just a plot point, but I can't play that because I have a father. And I know my father would never be like that. And as a father myself, I would never be able to NOT attack those gangsters. I want to do movies that show who I am as a human being."

Poitier called Martin Baum who said they will pay $750 for the part. ($7,000 today). He told Baum, " I read it and I can't play it," and explained why. Baum said, “That’s why you don't want to do this? You need that money don't you?" Poitier desperately needed the money. He had to pay the hospital $75 for his 2nd daughter's birth. But didn't take the part. Poitier said, "That speaks to who I was then and still am. And who I am is my father's son. I saw how he treated my mother and family. I know how to be a decent human being.

So I pawned my furniture, such as it was, got $75 and paid the hospital. Then I went back to dish washing. "Months later, Martin Baum called me and invited me to his office and said, "I have never been able to understand why you turned down that job. I told him why again, but I don't know if he understood it.

But Martin said, 'I have decided that anyone as crazy as you are, I want to be their agent.' He's been my agent till now." Poitier won an Academy Award for Best Actor for 'Lilies of the Field' in 1963. Five years later, Sidney Poitier was offered the lead in 'In the Heat of the Night' to be produced by Walter Mirisch (West Side Story, The Magnificent 7) Poitier said, "When I read the script, I said, 'Walter I can’t play this. The scene requires me to be slapped by a wealthy man and I just look at him fiercely and walk away. That is not very bright in today's culture. It's dumb.

"This is 1968. You can't do that. The black community will look at that and be appalled, because the human response would be different. You certainly won't do the movie with me this way. 'If I do this movie, I insist to respond as a human being; he pops me and I pop him right back. If you want me to play it, you will put that in writing. Also in writing you will say 'If this picture plays in the south, that scene is never removed.' Walter said, 'Yeah, I promise you that and I'll put it in writing.' "But being the kind of guy Walter is, his handshake and his word are the same, so I didn't need to have it in writing, and he kept his word. That scene made the movie. Without it, the movie wouldn't have been as popular."

'In the Heat of the Night' won five Academy Awards: Best Picture - Best Screenplay.

Sidney Poitier was a 20 year old dishwasher in NYC. He came from the Bahamas and could only read 3rd grade level, having great trouble with 3 syllable words. He lost his dish washing job, so he looked in the want ads and was about to throw the newspaper into the trash box on the street when he read: Actors Wanted.

The 'wanted' seemed like an invitation, so he walked to the address, was given a two page scene to read by a large man. Poitier slowly read word by word in his Caribbean accent. The large man grabbed him by the belt and collar and pushed him to the door saying, "Stop wasting people's time. You can't speak and you can't read.

Go back to dish washing." Walking to the bus stop Poitier stopped on the street thinking, "How did he know I was a dishwasher?" Poitier said: "I realized that was his perception of me. No value but something I could do with my hands. Even though he was correct in his anger to characterize me that way, I was deeply offended. I said to myself, 'I have to rectify that.' "I decided right then on that street, that I was going to be an actor just to show him he was wrong about me. I had to take the responsibility to change how people perceived me.

I continued as a dishwasher, but I began to work on myself."

Poitier auditioned at the American Negro Theater in Harlem, hoping to get into classes there. He didn't know that one could buy books with plays in them, so he memorized an article in True Confessions magazine.

He wasn't accepted, but Sidney said, "I'll be your janitor for free if you let me study here." The school accepted that deal. Months later, he was told he had no gift for acting and had to leave. Unknown to Poitier, three fellow students that liked him went to the head-master and asked her to give him a walk on in the next play. She said, "No, but I'll make him the understudy for the lead. (She had no intention to use him).

However, the night of the play, the lead, Harry Belafonte, had to help his janitor father carry out the six heavy boxes of furnace ashes, and it had to be done that night. So Poitier went on, knew his lines and did he best he could. In the theater that night was a producer that offered him a bit part in his next play. His character was the first to speak as an excited man who has to tell some news in the first scene, and that was all.

Poitier said, "When I looked out through a peephole at the 1,200 people waiting for the play to begin, I became paralyzed with fear. "I ran out on stage and started with my 7th line first. The other actor's eyes bulged out, but he came up with the right answer. We skipped around lines, then my character left the stage and that was my only scene. The audience didn't know the play, so they liked my confused, excited character.

"However, walking back to the room I was renting, I decided to give up on acting. I bought four newspapers on the way home and was surprised that I was mentioned favorably in three of them, like: 'Who was that funny kid that came on at the beginning?' So I decided to continue acting." After a few small parts in small movies, it was 1954. Sidney Poitier was sent to an audition for a movie by an agent named Martin Baum, but was not Poitier's agent.

Poitier read a scene in front of the producers, they wanted him and gave him a full script to take home. Poitier's character was a janitor who saw a crime committed by gangsters. To keep him quiet, the gangsters kill his daughter. And he stays quiet. Poitier said, "I really hated it. At that time, I had no objections to playing a janitor, but I hated the idea of a father not taking action on the gangsters. The janitor permits what the gangster do to him. To the writers it's just a plot point, but I can't play that because I have a father. And I know my father would never be like that. And as a father myself, I would never be able to NOT attack those gangsters. I want to do movies that show who I am as a human being."

Poitier called Martin Baum who said they will pay $750 for the part. ($7,000 today). He told Baum, " I read it and I can't play it," and explained why. Baum said, “That’s why you don't want to do this? You need that money don't you?" Poitier desperately needed the money. He had to pay the hospital $75 for his 2nd daughter's birth. But didn't take the part. Poitier said, "That speaks to who I was then and still am. And who I am is my father's son. I saw how he treated my mother and family. I know how to be a decent human being.

So I pawned my furniture, such as it was, got $75 and paid the hospital. Then I went back to dish washing. "Months later, Martin Baum called me and invited me to his office and said, "I have never been able to understand why you turned down that job. I told him why again, but I don't know if he understood it.

But Martin said, 'I have decided that anyone as crazy as you are, I want to be their agent.' He's been my agent till now." Poitier won an Academy Award for Best Actor for 'Lilies of the Field' in 1963. Five years later, Sidney Poitier was offered the lead in 'In the Heat of the Night' to be produced by Walter Mirisch (West Side Story, The Magnificent 7) Poitier said, "When I read the script, I said, 'Walter I can’t play this. The scene requires me to be slapped by a wealthy man and I just look at him fiercely and walk away. That is not very bright in today's culture. It's dumb.

"This is 1968. You can't do that. The black community will look at that and be appalled, because the human response would be different. You certainly won't do the movie with me this way. 'If I do this movie, I insist to respond as a human being; he pops me and I pop him right back. If you want me to play it, you will put that in writing. Also in writing you will say 'If this picture plays in the south, that scene is never removed.' Walter said, 'Yeah, I promise you that and I'll put it in writing.' "But being the kind of guy Walter is, his handshake and his word are the same, so I didn't need to have it in writing, and he kept his word. That scene made the movie. Without it, the movie wouldn't have been as popular."

'In the Heat of the Night' won five Academy Awards: Best Picture - Best Screenplay.

Sidney Poitier was a 20 year old dishwasher in NYC. He came from the Bahamas and could only read 3rd grade level, having great trouble with 3 syllable words. He lost his dish washing job, so he looked in the want ads and was about to throw the newspaper into the trash box on the street when he read: Actors Wanted.

The 'wanted' seemed like an invitation, so he walked to the address, was given a two page scene to read by a large man. Poitier slowly read word by word in his Caribbean accent. The large man grabbed him by the belt and collar and pushed him to the door saying, "Stop wasting people's time. You can't speak and you can't read.

Go back to dish washing." Walking to the bus stop Poitier stopped on the street thinking, "How did he know I was a dishwasher?" Poitier said: "I realized that was his perception of me. No value but something I could do with my hands. Even though he was correct in his anger to characterize me that way, I was deeply offended. I said to myself, 'I have to rectify that.' "I decided right then on that street, that I was going to be an actor just to show him he was wrong about me. I had to take the responsibility to change how people perceived me.

I continued as a dishwasher, but I began to work on myself."

Poitier auditioned at the American Negro Theater in Harlem, hoping to get into classes there. He didn't know that one could buy books with plays in them, so he memorized an article in True Confessions magazine.

He wasn't accepted, but Sidney said, "I'll be your janitor for free if you let me study here." The school accepted that deal. Months later, he was told he had no gift for acting and had to leave. Unknown to Poitier, three fellow students that liked him went to the head-master and asked her to give him a walk on in the next play. She said, "No, but I'll make him the understudy for the lead. (She had no intention to use him).

However, the night of the play, the lead, Harry Belafonte, had to help his janitor father carry out the six heavy boxes of furnace ashes, and it had to be done that night. So Poitier went on, knew his lines and did he best he could. In the theater that night was a producer that offered him a bit part in his next play. His character was the first to speak as an excited man who has to tell some news in the first scene, and that was all.

Poitier said, "When I looked out through a peephole at the 1,200 people waiting for the play to begin, I became paralyzed with fear. "I ran out on stage and started with my 7th line first. The other actor's eyes bulged out, but he came up with the right answer. We skipped around lines, then my character left the stage and that was my only scene. The audience didn't know the play, so they liked my confused, excited character.

"However, walking back to the room I was renting, I decided to give up on acting. I bought four newspapers on the way home and was surprised that I was mentioned favorably in three of them, like: 'Who was that funny kid that came on at the beginning?' So I decided to continue acting." After a few small parts in small movies, it was 1954. Sidney Poitier was sent to an audition for a movie by an agent named Martin Baum, but was not Poitier's agent.

Poitier read a scene in front of the producers, they wanted him and gave him a full script to take home. Poitier's character was a janitor who saw a crime committed by gangsters. To keep him quiet, the gangsters kill his daughter. And he stays quiet. Poitier said, "I really hated it. At that time, I had no objections to playing a janitor, but I hated the idea of a father not taking action on the gangsters. The janitor permits what the gangster do to him. To the writers it's just a plot point, but I can't play that because I have a father. And I know my father would never be like that. And as a father myself, I would never be able to NOT attack those gangsters. I want to do movies that show who I am as a human being."

Poitier called Martin Baum who said they will pay $750 for the part. ($7,000 today). He told Baum, " I read it and I can't play it," and explained why. Baum said, “That’s why you don't want to do this? You need that money don't you?" Poitier desperately needed the money. He had to pay the hospital $75 for his 2nd daughter's birth. But didn't take the part. Poitier said, "That speaks to who I was then and still am. And who I am is my father's son. I saw how he treated my mother and family. I know how to be a decent human being.

So I pawned my furniture, such as it was, got $75 and paid the hospital. Then I went back to dish washing. "Months later, Martin Baum called me and invited me to his office and said, "I have never been able to understand why you turned down that job. I told him why again, but I don't know if he understood it.

But Martin said, 'I have decided that anyone as crazy as you are, I want to be their agent.' He's been my agent till now." Poitier won an Academy Award for Best Actor for 'Lilies of the Field' in 1963. Five years later, Sidney Poitier was offered the lead in 'In the Heat of the Night' to be produced by Walter Mirisch (West Side Story, The Magnificent 7) Poitier said, "When I read the script, I said, 'Walter I can’t play this. The scene requires me to be slapped by a wealthy man and I just look at him fiercely and walk away. That is not very bright in today's culture. It's dumb.

"This is 1968. You can't do that. The black community will look at that and be appalled, because the human response would be different. You certainly won't do the movie with me this way. 'If I do this movie, I insist to respond as a human being; he pops me and I pop him right back. If you want me to play it, you will put that in writing. Also in writing you will say 'If this picture plays in the south, that scene is never removed.' Walter said, 'Yeah, I promise you that and I'll put it in writing.' "But being the kind of guy Walter is, his handshake and his word are the same, so I didn't need to have it in writing, and he kept his word. That scene made the movie. Without it, the movie wouldn't have been as popular."

'In the Heat of the Night' won five Academy Awards: Best Picture - Best Screenplay.

0 Comments

0 Shares

1122 Views